RL for High-Performance Jumping

Used a curriculum learning framework to teach simulation quadrupeds to jump. Worked on and written with Aryan Naveen and Pranay Varada. Completed for CS1840 - Introduction to Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

Agents acting in dynamic environments must be able to adapt to the conditions of these environments. Quadrupedal robots are particularly useful for simulating agents in these environments because of their flexibility and real‑world applicability. This reinforcement learning project aims to teach a quadruped to jump over a moving obstacle, using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and a two‑stage curriculum learning framework. Stage I focuses on achieving the ideal jumping motion, while Stage II integrates dynamic obstacles, utilizing a Markov Decision Process (MDP) modified to include motion dynamics and obstacle detection. Reference state initialization (RSI) and domain randomization are employed to enhance robustness and generalization. Simulations in IsaacGym demonstrated that two‑stage curriculum learning improved upon direct training in minimizing obstacle collisions, particularly for obstacles at closer ranges. Timing remains a challenge when attempting to avoid obstacles initialized from farther away. This work highlights the value of curriculum learning methods in RL for robotic tasks and proposes future improvements in reward shaping and learning strategy for enhanced adaptability in dynamic environments.

Introduction

Throughout the field of reinforcement learning, there is significant demand for creating strategies to learn an optimal policy that can achieve a desired reward across changing environments. Furthermore, it is essential that such a policy can understand the changes in these environments and act accordingly. After all, many environments in the real world are non‑stationary, with varying conditions in weather and terrain acting on agents, for example. Adaptive policies are also suitable for long‑term success because of their higher levels of robustness. In use cases from search‑and‑rescue operations to industrial inspections, such adaptability can be critical.

Our project aims to solve this problem of understanding changing environments through teaching a quadruped to react to an obstacle moving towards it with a random angle and velocity. Quadrupedal robots such as Boston Dynamics’ Spot and ANYbotics’ ANYmal are particularly advantageous for undertaking such a project for three reasons. First, there is extensive literature on reinforcement learning for quadruped locomotion, which means that we can iterate on different implementations of RL strategies in order to solve new problems. Specifically, while quadrupedal jumping may be well studied, our project aims to understand how an agent can react to random timing and position. Second, simulations of quadruped movement are both high‑dimensional and visually easy to comprehend, making it clear what the agent has learned once the training process is complete. Third, there is a strong basis for quadruped simulation and translation to real‑world situations where changing environments may be at play; a desire to understand environments motivated our decision to work on this project.

To tackle the particular scenario of jumping over a moving obstacle, we consider several RL techniques. We begin with Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) as the foundational approach, and subsequently integrate curriculum learning strategies into the training process to systematically optimize the quadruped’s ability to master this (perhaps surprisingly) complex task. Curriculum learning breaks this task down into sub‑problems, such that the quadruped first learns how to jump, and once it has mastered that skill, learns how to jump over a moving obstacle.

Preliminaries

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is a policy‑gradient method that improves upon previous methods in the literature through its relative ease of implementation—requiring just first‑order optimization—and greater robustness relative to optimization techniques such as Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) (Schulman et al., 2017). While the objective function maximized by TRPO is the expectation of the product of the advantage and a probability ratio measuring the change between the new and old policy at an update, PPO’s objective function clips the probability ratio in this surrogate objective in order to prevent the policy from making unstable updates while simultaneously continuing to allow for exploration. Clipping also avoids having to constrain the KL divergence, making the process computationally simpler and enabling policy updates over multiple epochs. PPO’s simplicity and stability make it a commonplace strategy for finding the optimal policy in RL, which is why we use it as a baseline from which we search for possible improvements, namely curriculum learning methods.

Literature Review

Atanassov, Ding, Kober, Havoutis, and Santina use curriculum learning to stratify the problem of quadrupedal jumping into different sub‑tasks, in order to demonstrate that reference trajectories of mastered jumping are not necessary for learning the optimal policy in this scenario (Atanassov et al., 2024). This increases the adaptability of such a policy, because it is learned by the robot on its own, enabling it to generalize better to unseen real‑world scenarios. Another important component of achieving the optimal policy is reward shaping, which Kim, Kwon, Kim, Lee, and Oh tackle in a stage‑wise fashion in the context of a humanoid backflip (Kim et al., 2024). By developing customized reward and cost definitions for each element of a successful backflip, a complex maneuver like this is segmented into an intuitive fashion that translates well to real‑world dynamics.

Problem Formulation

We utilize a Markov Decision Process (MDP) as the underlying sequential decision‑making model for our RL problem. The MDP is described as a tuple

\(\mathcal{M} = (\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{A}, r, P, \rho, \gamma)\)

where:

- $\mathcal{S}$ is the state space

- $\mathcal{A}$ is the action space

- $r: \mathcal{S}\times\mathcal{A}\to\mathbb{R}$ is the reward function

- $P: \mathcal{S}\times\mathcal{A}\to\Delta(\mathcal{S})$ is the transition operator

- $\rho\in\Delta(\mathcal{S})$ is the initial distribution

- $\gamma\in(0,1)$ is the discount factor

The overall objective of reinforcement learning is to find a policy $\pi:\mathcal{S}\to\mathcal{A}$ that maximizes the cumulative infinite‑horizon discounted reward:

\(\mathbb{E}_{s_0\sim\rho,\pi}\Bigl[\sum_{i=0}^\infty \gamma^i\,r(s_i,a_i)\,\Bigm|\,s_0\Bigr].\)

A given policy $\pi$ has a value function under transition dynamics $P$ defined as

\(V^\pi_P(s)=\mathbb{E}_\pi\Bigl[\sum_{i=0}^\infty \gamma^i\,r(s_i,a_i)\mid s_0=s\Bigr],\)

and the state‑action value function is similarly defined as

\(Q^\pi_P(s,a)=\mathbb{E}_\pi\Bigl[\sum_{i=0}^\infty \gamma^i\,r(s_i,a_i)\mid s_0=s,\;a_0=a\Bigr].\)

Quadruped Jumping Obstacle Avoidance MDP

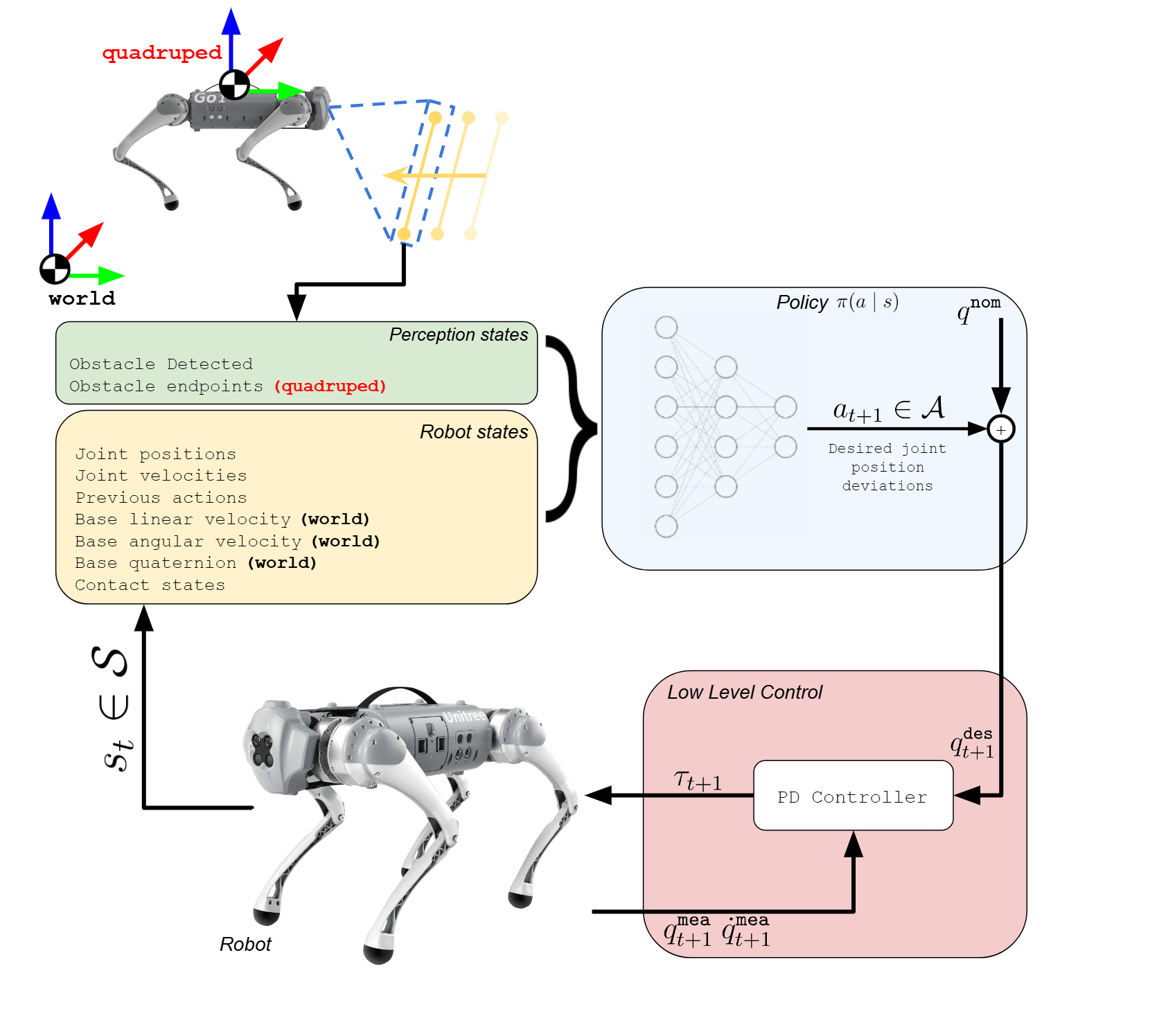

As outlined in the introduction, in this report we extend the work of (Atanassov et al., 2024) to enable a quadruped to jump over dynamic obstacles. This enhancement requires not only integrating curriculum learning, but also modifying the underlying MDP formulation to account for the quadruped’s perception module’s feedback as shown in Figure 1.

State Space

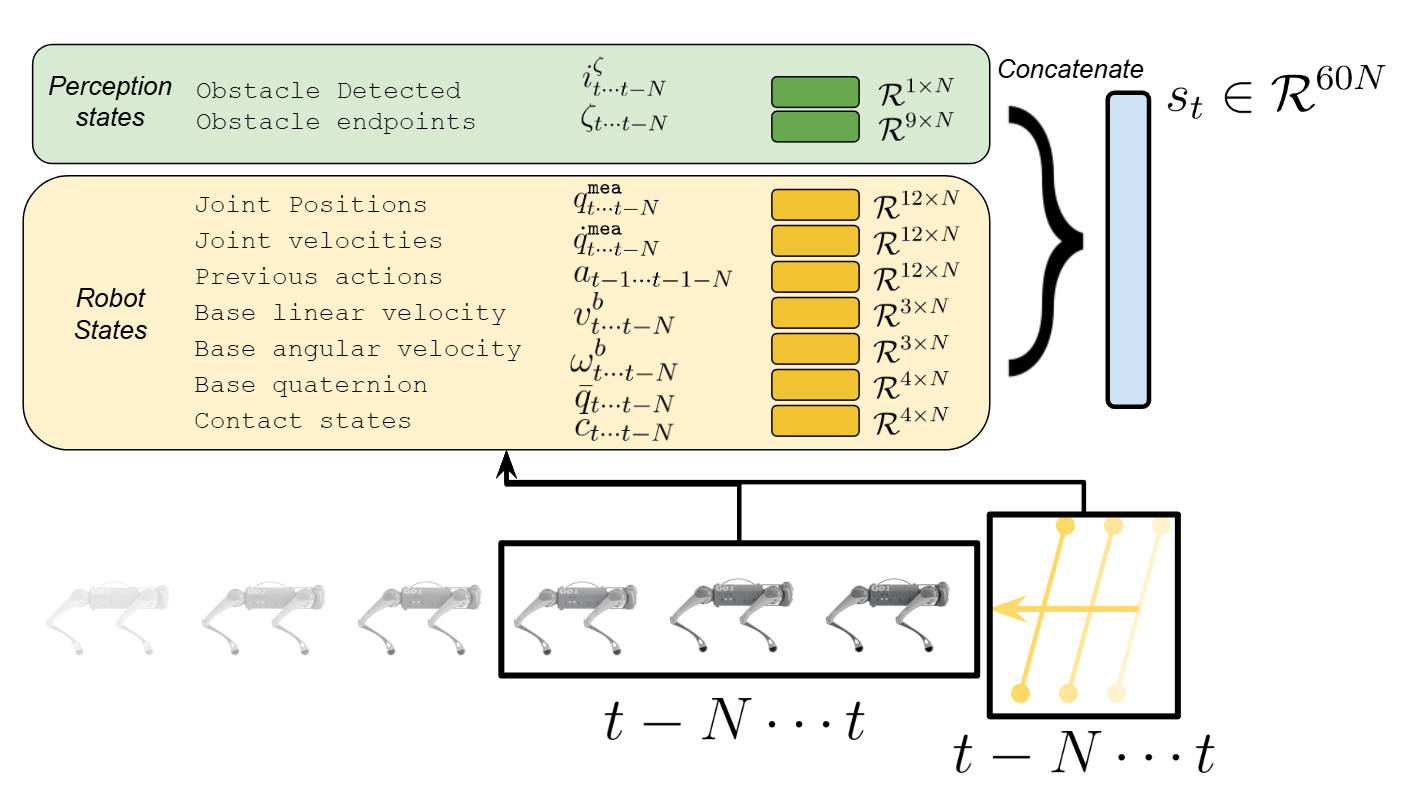

Building on (Atanassov et al., 2024), we leverage a memory of previous observations and actions to enable the agent to implicitly reason about its own dynamics. We concatenate over a window of $N$ timesteps:

- Base linear velocity $\mathbf{v}\in\mathbb{R}^{3\times N}$

- Base angular velocity $\boldsymbol{\omega}\in\mathbb{R}^{3\times N}$

- Joint positions $\mathbf{q}\in\mathbb{R}^{12\times N}$ and velocities $\dot{\mathbf{q}}\in\mathbb{R}^{12\times N}$

- Previous actions $\mathbf{a}_{t-1}\in\mathbb{R}^{12\times N}$

- Base orientation $\bar{q}\in\mathbb{R}^{4\times N}$

- Foot contact states $\mathbf{c}\in\mathbb{R}^{4\times N}$

To handle dynamic obstacles, we add obstacle detection flags $i^\zeta$ and obstacle endpoints $\zeta$—each also tracked over $N$ frames—resulting in a total dimension of $60N$.

Action Space

As is standard in quadruped policies, our policy generates the desired twelve actuated joint angles $\mathbf{q}^{\texttt{des}} \in \mathbb{R}^{12}$ for control. Specifically, the policy learns the deviation from the nominal joint positions $\mathbf{q}^{\texttt{nom}} \in \mathbb{R}^{12}$. Additionally, it is standard for the output actions to be smoothened utilizing a low-pass filter and then scaled before being added to $\textbf{q}^{\texttt{nom}}$ to compute the $\textbf{q}^{\texttt{des}}$ for the motor servos. As visualized in Figure 1, a low level controller is utilized to compute the necessary joint torques to attain the computed setpoints.

Reward

Inspired by (Atanassov et al., 2024), we define \(r_{\mathrm{total}} = r^+ \exp\!\Bigl(-\|\;r^-\;\|^2/\sigma\Bigr)^4,\) where positive components $r^+$ are multiplied by an exponential penalty on the negative components $r^-$. This allows for the observed reward to remain positive, where incurred penalties scale down the observe reward to improve stability, helping to combat local minimas such as standing behaviors without jumping to avoid energy penalties.

- Dense rewards: tracking flight velocity, squat height, foot clearance, and penalizing energy use.

- Sparse rewards: episode‑level bonuses for successful jumps and penalties for fall‑over, collision, or large orientation errors.

State Initialization & Domain Randomization

An important aspect of such an MDP formulation is selecting the initial state distribution, which we will represent $\rho(\mathcal{S})$. When applying learning methods to agents such as quadrupeds, for many tasks it is convenient to initialize the agent in a static state in the learning process. However, for certain tasks such as quadruped jumping, such an initial state distribution is undesirable when a lack of diverse and informative initial states discourages the agent from exploring desired trajectories. Consider the quadruped jumping scenario in which termination penalties are applied to the reward function when the quadruped falls over. Having not yet learned how to stick a landing, the agent sees that jumping high leads to a large penalty and stops attempting to learn to jump high. Further, static initialization can make it difficult for a policy to learn that certain states have high rewards. In the quadruped jumping example, if the quadruped is always initialized on the floor, the policy never sees that height off of the floor is associated with high positive rewards.

To combat such scenarios, Peng, Abeel, Levine, and van de Panne introduce a strategy of reference state initialization (RSI) (Peng et al., 2018). This method of state initialization is an imitation learning technique in which the agent’s initial state is sampled from the reference trajectory it is trying to learn. More formally, for reference expert trajectory \(\tau_{ref} = \{s^{ref}_0, (s^{ref}_1, a^{ref}_1)\dots (s^{ref}_{H-1}, a^{ref}_{H-1})\}\), \(\rho(\{s^{ref}_0\dots s^{ref}_{H-1}\})\) is given by some distribution across the values of $s^{ref}$. The agent then encounters desirable states along the expert trajectory, even before the policy has acquired the proficiency needed to reach those states (Peng et al., 2018).

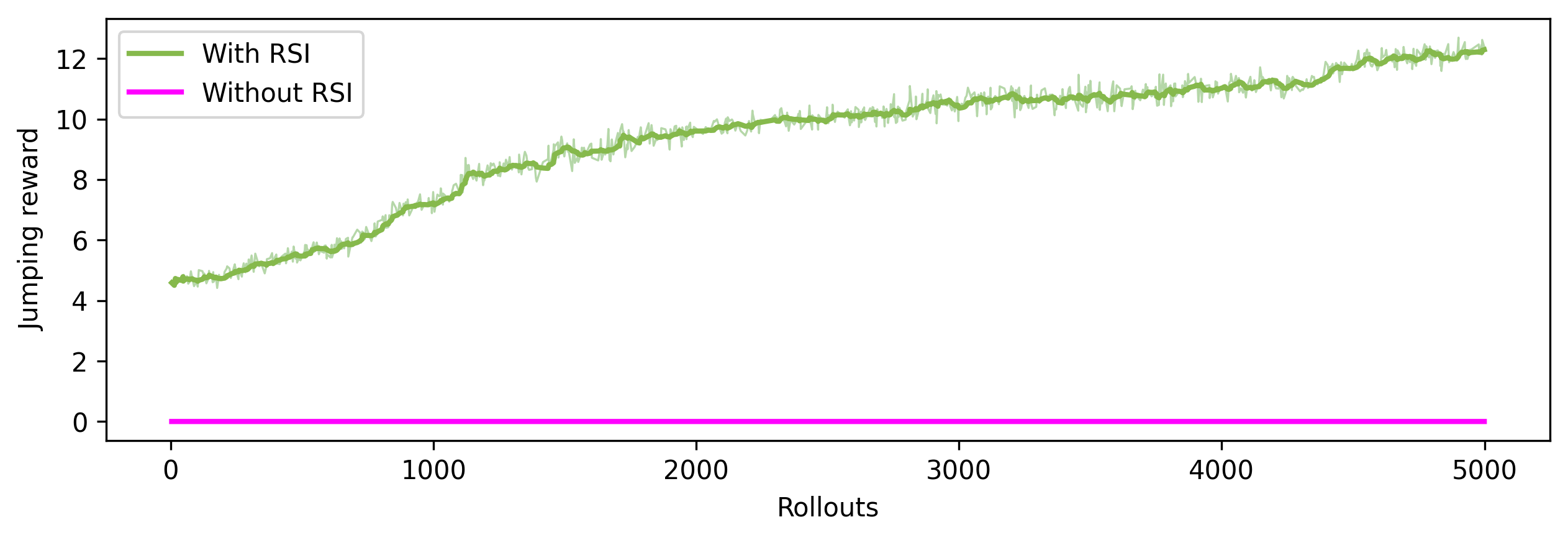

In their quadruped jumping formulation, Atanassov, Ding, Kober, Havoutis and Santina use a modified version of RSI in which they sample a random height and upward velocity from a predefined range rather than using an explicit reference trajectory (Atanassov et al., 2024). Since there is no reference trajectory, we want an intelligent choice of $S_{init}\subset S$ such that \(s_0\sim \rho(\mathcal{S}_{init})\) for the given task. In our case, \(s_0\sim \mathcal{U}(\mathcal{S}_{init})\) where $\mathcal{U}$ represents the uniform distribution and $\mathcal{S}_{init}$ takes the range of values shown in table Table 1 for stage I training. It should be noted that for stage I training, all components of the state space that are properties of the obstacle are set to 0. To highlight the importance of RSI, Figure 4 demonstrates the impact of implementing RSI in the first stage.

| State Variable | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|

| Height (m) | 0 | 0.3 |

| $z$-velocity (m/s) | -0.5 | 3 |

Table 1: Initialization ranges for Stage I

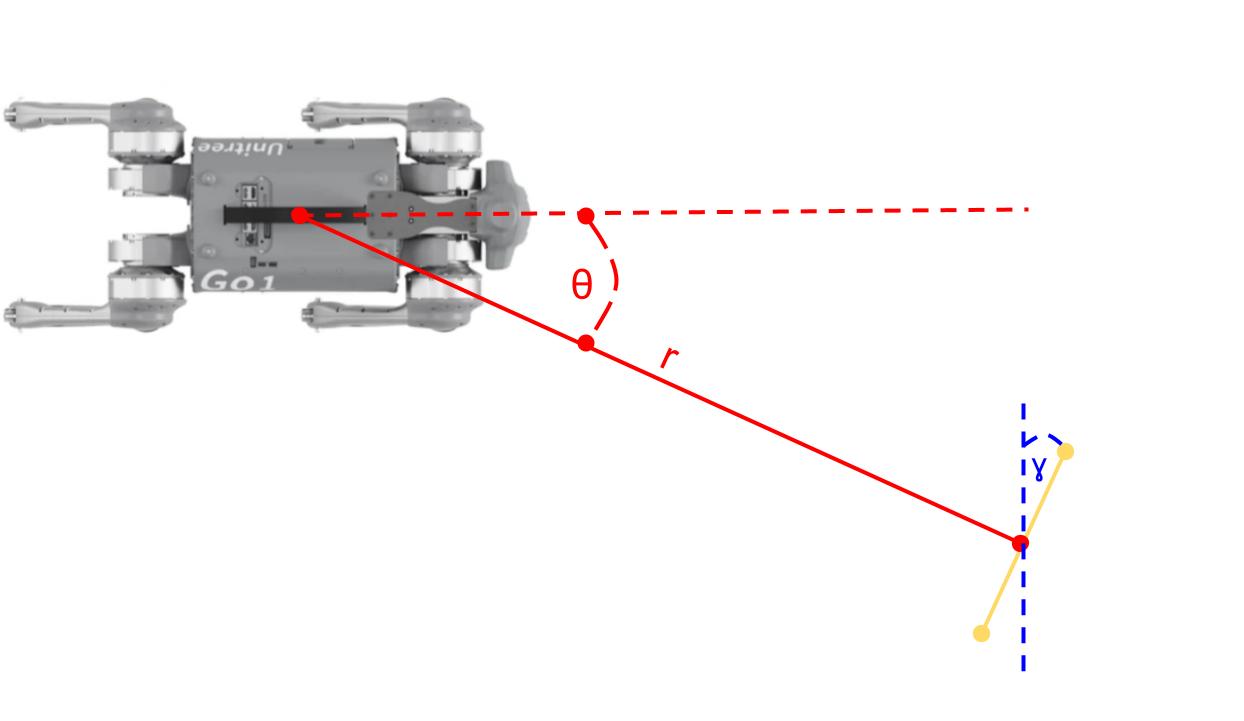

In addition to using this modified RSI for the quadruped itself, we further utilize randomization of obstacle states in $s_0$ in the second stage of learning. Ranges for $\mathcal{S}_{init}$ are given in Table 2 for stage II training. Here RSI is necessary so that the quadruped learns to jump over obstacles moving at various speeds and with any distance or orientation. An interpretation of the obstacle characteristics is given in Figure3.

| State Variable | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|

| Obstacle distance $r$ (m) | 3 | 7 |

| Obstacle direction $\theta$ (rad) | 0 | $2\pi$ |

| Obstacle orientation $\gamma$ (rad) | $\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta-\frac{\pi}{3}$ | $\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta+\frac{\pi}{3}$ |

| Obstacle velocity (m/s) | 3.5 | 7 |

Table 2: Initialization ranges for Stage II

In addition to RSI, a related technique called domain randomization is often utilized for policies training in a simulation environment in an attempt to allow for maximum real-world generalization and decrease the sim-to-real gap. This concept was introduced by Tobin, Fong, Ray, Schneider, Zaremba, and Abbeel, wherein instead of training a model on a single simulated environment, the simulator is randomized to expose the model to a wide range of environments at training time (Tobin et al., 2017). The original reinforcement learning quadruped environment we built upon includes zero-shot domain randomization for ground friction, ground restitution, additional payload, link mass factor, center of mass displacement, episodic latency, extra per-step latency, motor strength, joint offsets, PD gains, joint friction, and joint damping (Atanassov et al., 2024).

Obstacle Avoidance Curriculum Learning

Curriculum learning, generally attributed to Bengio, Louradou, Collober, and Weston, is a sequential method of model training wherein the model is first taught a simple task or building block and then goes on to be trained on more difficult problems that require the building blocks (Bengio et al., 2009). This method of training a network is an intuitive model for how humans learn complex tasks: students first learn basic math, then use those tools to learn algebra, then use those tools to learn calculus, and so on. Such a learning procedure has been shown to be especially useful for reinforcement learning (Narvekar et al., 2020). Sample efficiency is often vastly improved as the agent learns useful representations and behaviors early in training before moving to more difficult tasks. Stable partial solutions reduce high variance in returns and prevent the agent from getting stuck in poor local optima when faced with complex versions of the task. Because the agent has a sequence of diverse learning experiences, it often generalizes better to new or slightly different tasks.

In the context of quadruped tasks involving jumps, Peng, Abeel, Levine, and van de Panne use curriculum learning in the following manner: stage I teaches the quadruped how to jump, stage II teaches the quadruped how to jump to a desired position and orientation, and stage III teaches the quadruped how to jump onto or over platforms (Atanassov et al., 2024). For our task, we utilize the same stage I training to teach the quadruped how to jump in place. However, instead of making the robot motion more difficult such as the original experiments, we make the next stage more difficult by introducing a flying obstacle to the environment. Accordingly, the reward function is updated to include a sparse penalty and termination for collision with the obstacle. The sparse reward calculation is given below, where $\zeta$ represents the obstacle and the reward scale is -50.

\[r_{\mathrm{col}} = \mathbb{1}\bigl\{\min_{f\in\text{feet}}\|\mathbf{f}-\zeta\|\le0.1\bigr\}.\]Another important distinction is that, unlike the original experiments, our agent is not randomly returned to stage \Romannum{1} while training later stages. In the original work, the authors wanted to maintain a more “ideal” jumping motion while learning the later tasks, but our objective mostly values clearing the flying obstacle. A “worse” jumping form is more desirable here, as taking the time to enter an athletic stance sometimes allows a fast-moving obstacle to hit the quadruped before it is able to leave the ground. To reflect this, we decrease the reward scale for crouching in an athletic position before jumping in the second stage from 5 to 1. The reward for crouching to the desired height for an athletic stance is given below.

\[r_{squat}=0.6\exp\left(-\frac{(\text{height}-0.2)^2}{0.001}\right)\]Experiments

In our experimental setup, we primarily tested two different strategies for discerning the optimal policy for jumping over a moving obstacle. Firstly, our “control” was training without curriculum learning (20,000 iterations). This process essentially skipped our aforementioned stage I, such that the quadruped would go straight to attempting to master jumping over a moving obstacle. The performance of the curriculum learning-free method served as a baseline for our second strategy: 5,000 iterations in stage I – with no dynamic obstacle present – such that the quadruped would learn to jump in place, followed by 15,000 iterations in stage II with the dynamic obstacle in place, through which the quadruped would ideally use its ability to jump to learn how to jump over this obstacle. We chose these particular numbers of iterations because the policy converged after 5,000 iterations in stage I, and we assumed that stage II would be more difficult. In both cases we utilize the same network architecture in order to isolate the learning algorithms performance.

Training Environment

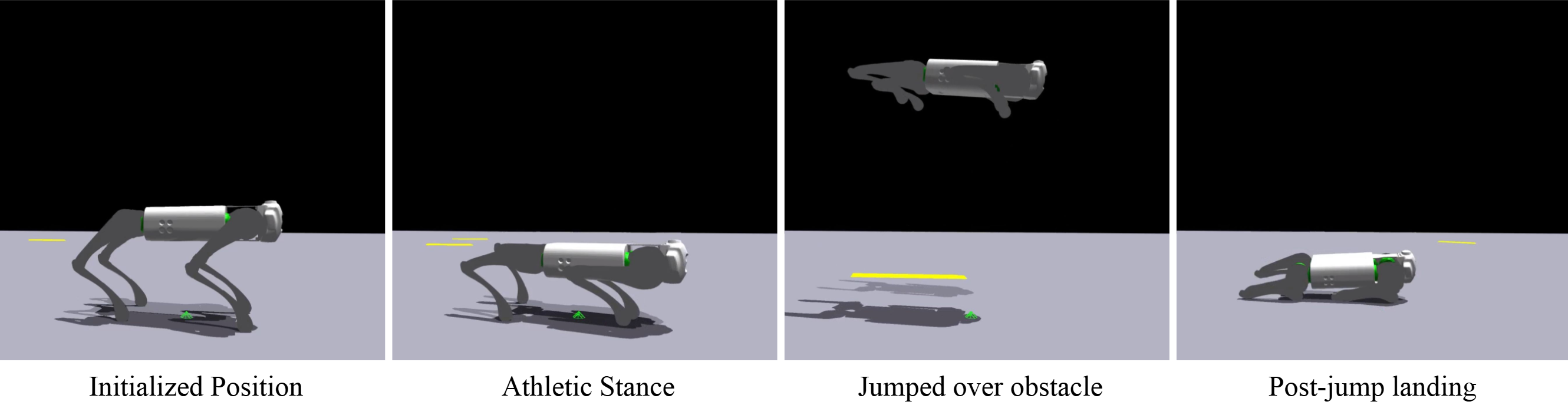

We train our policies in IsaacGym because of its speed and scalability, resulting from the capability to sample multiple environments in parallel. IsaacGym enables massive parallelism by simulating thousands of environments simultaneously on a single GPU, reducing training time. Its seamless integration with PyTorch and support for high-fidelity physics make it an ideal platform for developing and testing policies in dynamic and complex environments. This efficiency and realism allow us to iterate quickly and deploy robust, high-performing policies. Additionally, IsaacGym offered preexisting support for several quadrupedal-based robot environments, which allowed our research to focus purely on the learning algorithms rather than simulator design. As shown in Figure 6, we are able to train and evaluate realistic policies in IsaacGym.

Network Architecture

While utilizing PPO, both actor and critic network architectures are the same with only the output layer being different, with the former having 12 output neurons while the latter had 1 to approximate the $Q$ function.

Architecture. Three fully connected layers with $\lvert s \rvert$, 512, 512, and 12 neurons. Non-linear activations are included between each layer with a ReLU function. Sampled actions are normalized with a $tanH$ function to ensure that actions remain between -1 to 1 and then scaled appropriately.

Results

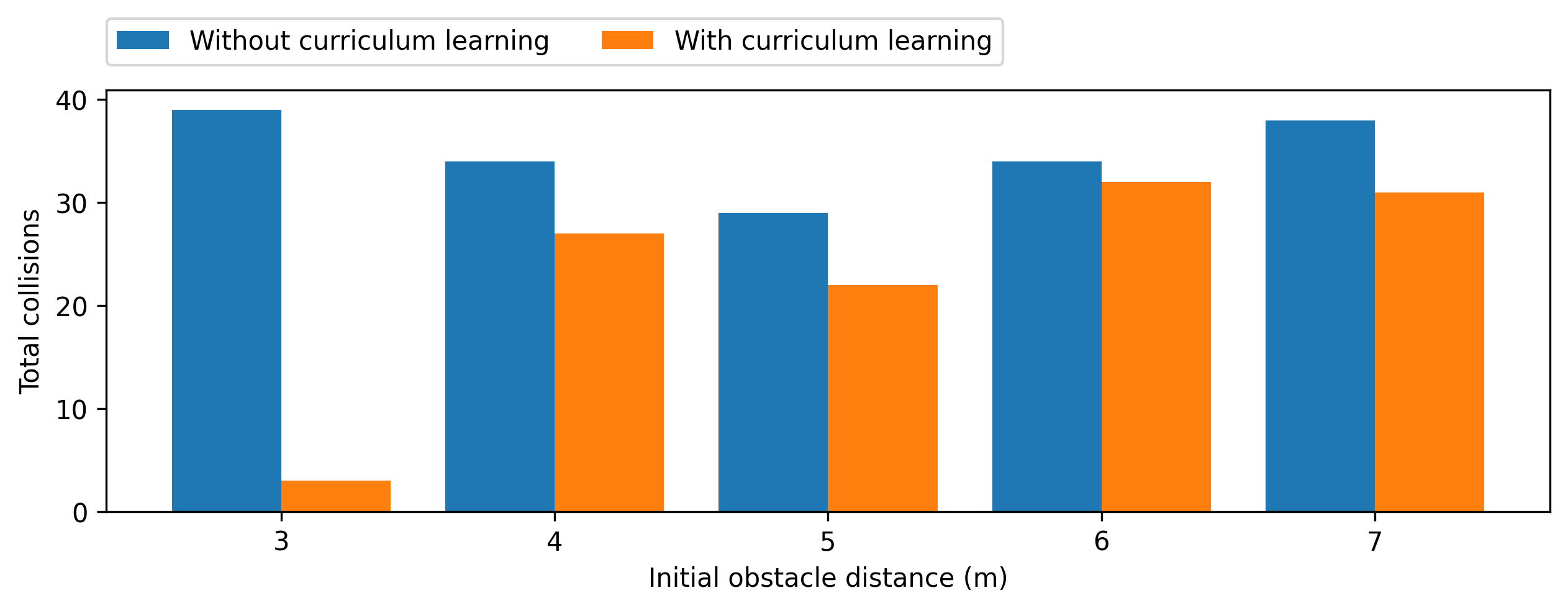

To compare these two methods, we looked at the number of times (out of 50) that the quadruped collided with an obstacle initialized at radii from 3m to 7m away at 1m increments. This range of distance provided suitable grounds of comparison between the two methods because the obstacle was not initialized too close to or far away from the quadruped. As Figure 5 shows, the curriculum learning method performed better than the method without curriculum learning across each initial distance, and markedly so at a radius of 3m away. While the quadruped failed to clear a majority of obstacles at longer radii, the results tell us that segmenting training into two sub-task sections can be at least somewhat effective in obstacle avoidance.

Why does the performance at longer radii leave much to be desired? Firstly, consider Figure 6, which demonstrates the quadruped jumping motion. We observed that the quadruped clearly learns how to jump – by settling into an athletic stance, propagating upwards from that stance, and landing decently well on its feet. It even learns how to jump over an obstacle it perceives, as demonstrated by its avoidance of all but three obstacles at a radius of 3 quadruped lengths. However, it is not clear that the quadruped has learned how to properly time its jump. It tends to jump as soon as it has perceived an obstacle, but at longer radii, this can result in a jump and a landing before the obstacle even arrives at the quadruped’s position, resulting in a collision. Therefore, in future training, it would be important to encourage patience: the quadruped should gauge the speed of the obstacle such that it jumps only when the obstacle is sufficiently close to be cleared in a single jump.

In addition, as mentioned previously, we do not desire the ideal jumping motion in this scenario, because we want to minimize the time the quadruped takes to enter an athletic stance. It could be that the curriculum learning process as currently constructed places too much emphasis on attaining the ideal jumping form, rather than simply learning how to jump and maximizing obstacle avoidance efficiency from there.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this work has demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of leveraging reinforcement learning and curriculum learning strategies to enable a quadrupedal robot to perform jumps over dynamic obstacles. With our formulated MDP using PPO as the baseline algorithm, we demonstrated that the structured, multi-stage approach of curriculum learning can feasibly be used to train agents in dynamic environments. The quadruped was guided through tasks with increasing difficulty, starting from basic jumping mechanics and eventually learning the more complex task of dodging flying obstacles.

Beyond curriculum learning, modified RSI was crucial to the project. RSI ensured that the quadruped encountered a broad distribution of initial states, including intermediate positions it would not naturally discover from a static start. This exposure accelerated learning and prevented the policy from converging prematurely to trivial but non-transferable behaviors. Domain randomization was also used, although to truly test its effects the policy should be implemented on a real quadruped to test generalization.

Finally, we utilize intelligent reward shaping to achieve the desired behavior in the second stage. The penalty for not maintaining an athletic stance was reduced to encourage the quadruped to prioritize timing and spatial awareness over good jumping form. Moreover, sparse penalties were introduced for collisions with the obstacle, reinforcing the importance of proactive avoidance strategies.

Overall, this project underscores the power of coupling advanced RL algorithms with principled training strategies. This being said, we note that there is room for significant improvement in the quadruped’s performance. Learning the timing of an optimal action is an inherently challenging problem for a MDP given issues like balancing time-horizon discount with the patience needed to account for slowly unfolding dynamic environments.

Future Directions

With more time, there are several different avenues we could pursue to iterate upon this project. Firstly, the obstacle in our experimental setup was guaranteed to pass through the quadruped’s position, so one interesting problem to solve would be teaching the quadruped to jump only when an obstacle will directly interfere with its position. In addition, our scenario mimics that of a human jump roping, so exploring the quadruped’s ability to perform multiple successive jumps – requiring not just proper jump timing but also a landing maneuver that enables the quadruped to reset for another jump – could be another scenario worth considering.

As far as increased performance in the current environment setup, we have several ideas. First, the reward-shaping for stage II could be improved to better encourage optimal timing of initial ground clearance. Second, RSI in its original format could be utilized by manually creating expert reference trajectories. Imitation learning strategies like DAgger could be implemented in a similar fashion. Finally, a predictive network for obstacle trajectory could be incorporated into the state space, potentially giving the policy better insight than obstacle properties alone.

Returning to our motivation, solving problems like these using curriculum-based reinforcement learning strategies could easily be applicable in real-world scenarios, where obstacle avoidance is often essential for quadrupedal and humanoid robots alike. Breaking down multi-stage problems like clearing obstacles enables agents to learn a variety of skills.

References

2024

- Curriculum-Based Reinforcement Learning for Quadrupedal Jumping: A Reference-free Design2024

- Stage-Wise Reward Shaping for Acrobatic Robots: A Constrained Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning Approach2024

2020

- Curriculum Learning for Reinforcement Learning Domains: A Framework and Survey2020

2018

- DeepMimic: example-guided deep reinforcement learning of physics-based character skillsACM Transactions on Graphics, Jul 2018

2017

- Proximal Policy Optimization AlgorithmsJul 2017

- Domain Randomization for Transferring Deep Neural Networks from Simulation to the Real WorldJul 2017

2009

- Curriculum learningIn Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, Jul 2009